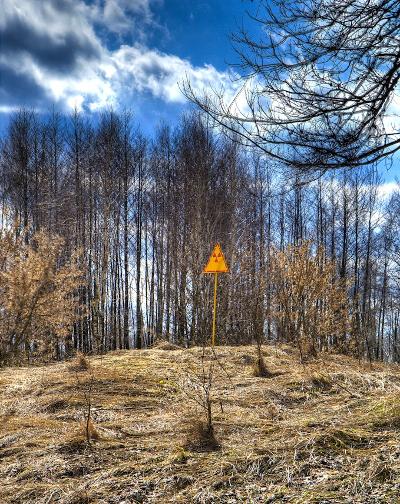

How do we talk about nature that has been affected by Chernobyl? What do we mean by it? This project considers the adjectives and thoughts presented about nature in various forms of writing, which points to how we perceive irradiated nature.

Introduction

Some catastrophes are an act of nature, and some are man-made. The repercussions for any catastrophe, however, are long lasting and can have a massive impact on many things—from the people involved to the tiniest creature or plant beneath our feet. Though we may not always consider it, nature can be affected just as strongly as humanity, and how people talk about nature in the context of catastrophe can be instrumental to understanding our own responses and views of events that have transpired around us. Here, using the Chernobyl disaster of 26 April 1986 as a lens, and considering the following ways in which it is described, let us discuss various perceptions of irradiated nature.

Vulnerability: Excerpts from “Abyssal Intimacies and Temporalities of Care” 1

The following selections of text come from an article called “Abyssal Intimacies and Temporalities of Care: How (Not) to Care about Deformed Leaf Bugs in the Aftermath of Chernobyl” by Astrid Schrader, a professor of sociology, philosophy, and anthropology. This article focuses on what makes people care about creatures other than themselves, and how they recognize those in need of our care and advocacy, and what exactly that looks like.

“Prompted by a classroom discussion on knowledge politics in the aftermath of the Chernobyl disaster, this article offers a reading of Hugh Raffles’ Insectopedia entry on Chernobyl. In that entry, Raffles describes how Swiss science-artist and environmental activist Cornelia Hesse- Honegger collects, studies, and paints morphologically deformed leaf bugs that she finds in proximity of nuclear power plants. In exploring how to begin to care about beings, such as leaf bugs, this article proposes a notion of care that combines an intimate knowledge practice with an ethical relationship to more-than-human others. Jacques Derrida’s notion of ‘abyssal intimacy’ is central to such a combination. Hesse-Honegger’s research practices enact and her paintings depict an ‘abyssal intimacy’ that deconstructs the oppositions between concerns about human suffering and compassion for seemingly irrelevant insects and between knowledge politics ethics. At the heart of such a careful knowledge production is a fundamental passivity, based on a shared vulnerability. An abyssal intimacy is not something we ought to recognize; rather, it issues from particular practices of care that do not identify their subjects of care in advance. Caring or becoming affected thus entails the dissociation of affection not only from the humanist subject, but also from movements in time: from direct helping action and from the assumption that advocacy necessarily means speaking for an other, usually assumed to be inferior.”

“The students responded emotionally; functional; relationships of co-dependence remained unconvincing but these relationships would not have been Raffles’ point: his entry is first of all about the vulnerability of leaf bugs and not (or only second) about their utility as possible biosensors for radiation risks to humans. But why would Raffles devote such a large portion of this chapter to Hesse-Honegger’s painting practice, and how did it relate to scientific expertise on the one hand, and forms of artistic expressions on the other, the students were wondering. In short, what has art to do with advocacy?”

“Under the microscope seeing becomes believing: Raffles (2010) quotes Hesse-Honegger, ‘Although I was theoretically convinced that radioactivity affects nature, I still could not imagine what it would actually look like. Now these poor creatures were lying there under my microscope. I was shocked’ (p. 21). While the deformities remained imperceptible to Raffles’ own untrained eyes, he reiterates, ‘[J]ust think, she says, what such and anomaly must feel, if you are only two tenths of an inch!’ (p. 15). Clearly imagining the pain of another takes some trained vision in this case. Even if empathy is always entangled with cognition as Lori Gruen (2012) suggests, it would require an initial emotional reaction. Can we imagine the pain of a leaf bug? (See Figure 1).”

Beauty: Excerpt from from Wormwood Forest2

A journalist by trade, Mary Mycio wrote Wormwood Forest: A Natural History of Chernobyl on the subject of reporting on her own visits to the Zone, seeing and describing what she saw as an area in recovery.

“PLUTONIUM SAFARI

The zone in late autumn was a subtle landscape, painted with a cool palette of green pines, pale yellow fields, and silvery birches capped with a filigree of copper branches. Bare willows provided bright splashed of orange the framed the road on an unusually sunny and warm November afternoon.”

Morbidity: Liubov Sirota’s poetry on Chernobyl3

Liubov Sirota is a Ukrainian poet and former resident of Pripyat—an eyewitness to the disaster and its aftereffects, who experiences them herself. The following lines come from a collection of her poems about Chernobyl.

Visit the interactive annotated poems on Professor Paul Brians’ faculty website

Change: Berry pickers in Polesia4

The article discussed here is by Kate Brown, a professor of history in the US, and Olha Marynyuk, a historian in Ukraine. Its subject are the berry pickers of a region called Polesia, specifically the part located in northern Ukraine. Though excluded from the exclusion zone, residents of this area still feel the effects of the radiation supposedly contained in a 30-kilometer radius around the Chernobyl nuclear power station. They are pushed to change their lifestyles to accommodate the radiation and still live.

Visit the interactive annotated article on Aeon.co

Conclusion

There are many ways in which people consider the aftermath of Chernobyl, and they can all be seen through looking at how people discuss the natural world as it relates to the disaster. This is a concept that is considered across disciplines, from poetry to academic articles, with some viewing the affected areas and nature as vulnerable, some beautiful, some morbid, and some as a large-scale change. And perhaps it is all of these things, perhaps it is more than this, and perhaps it is nothing. However, Chernobyl altered the world irrevocably, and the only thing that matters now is what humanity, through any lens and with any background, chooses to do about its effects.

Works Cited

-

Schrader, Astrid. “Abyssal Intimacies and Temporalities of Care: How (Not) to Care about Deformed Leaf Bugs in the Aftermath of Chernobyl.” Social Studies of Science. 45. 5 (2015): 665-675. ↩

-

Mycio, Mary. Wormwood Forest: A Natural History of Chernobyl. Washington, D.C.: Joseph Henry Press, 2005 101. ↩

-

Sirota, Liubov. “Chernobyl Poems by Liubov Sirota.” Common Errors in English Usage and More Chernobyl Poems by Liubov Sirota Comments, Washington State University, 5 Dec. 2016, brians.wsu.edu/2016/12/05/chernobyl-poems/. ↩

-

Brown, Kate. “The Harvests of Chernobyl.” Aeon.co. 29, Nov. 2016. ↩

Marit Eiler ‘20 is a Russian and Linguistics major at Bryn Mawr College.

RUSS043 Chernobyl: Nuclear Naratives and the Environment, Swarthmore College, Spring 2020