The Course – Chornobyl

We began the course by asking a seemingly straightforward question: What really happened at the Chornobyl Nuclear Power Plant? At our first meetings, we pieced together the basic facts of the disaster. On April 26, 1986, the operators of the Chornobyl Nuclear Power Station near Prypiat, Ukraine conducted a routine test of the reactor’s capacity to operate under reduced power. Due to a combination of operator error and faulty design, Reactor 4 exploded. The ensuing spread of radioactivity across Europe resulted in a mass evacuation, political turmoil, unprecedented ecological devastation, and, some would argue, the end of the Soviet Union.

Drawing on Svetlana Alexievich’s Voices from Chernobyl and Serhii Plokhy’s Chernobyl: The History of a Nuclear Catastrophe, we introduced questions that complicated our understanding of this historiography:

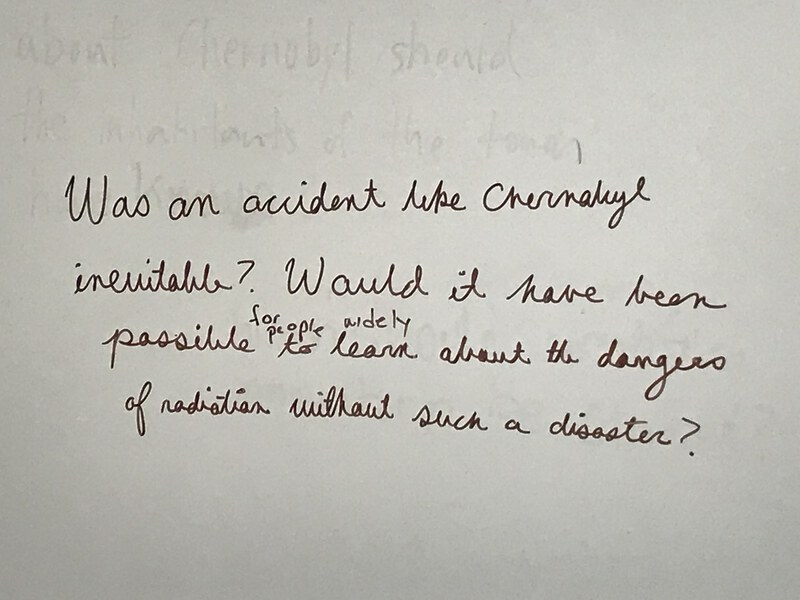

- How do historical accounts explain and limit the story of Chornobyl?

- How do oral testimonies complicate and/or reinforce dominant political, scientific, and historical explanations of Chornobyl?

- What can we really know about Chornobyl?

- How can Chornobyl be represented through language and art, if at all?

These questions about the role of historical narrative framed our study of memory in the aftermath of disaster. Survivors’ poetry provided us with the opportunity to interpret the catastrophe through the lens of metaphor, meter, and symbolism. We also thought about what it means to stage catastrophe by reading and performing scenes from Vladimir Gubaryev’s Sarcophagus: A Day’s Tragedy and Sergei Kurginian’s Compensation: A Liturgy of Fact. These works, which reflect a sense of spiritual alienation, motivated us to consider how disasters like Chornobyl simultaneously resist and necessitate memorialization and interpretation.

We revisited these topics in our conversations about Chornobyl’s potential geographical and political boundaries. By reading Christa Wolf’s Accident: A Day’s News alongside “anti-memoirs” written by Mohamed Makhzangi, an Egyptian doctor studying in Kiev in 1986, we discussed how catastrophe is experienced from a distance. Together, these conversations led to another central question: Who and what can bear witness to disaster?

The tensions between international politics, governmental rhetoric, and the uncontrollable spread of Chornobyl narratives served as the foundation of our study of media and conspiracy theories. Julia Voznesenskaya’s novel The Star Chernobyl interrogates how the suppression of information challenged Soviet citizens to reevaluate their relationship to the state. Later in the semester, Chad Gracia’s documentary The Russian Woodpecker depicted how a Ukrainian artist’s obsession with a conspiracy theory about Chornobyl connects to the Soviet Union’s lingering political and social ghosts.

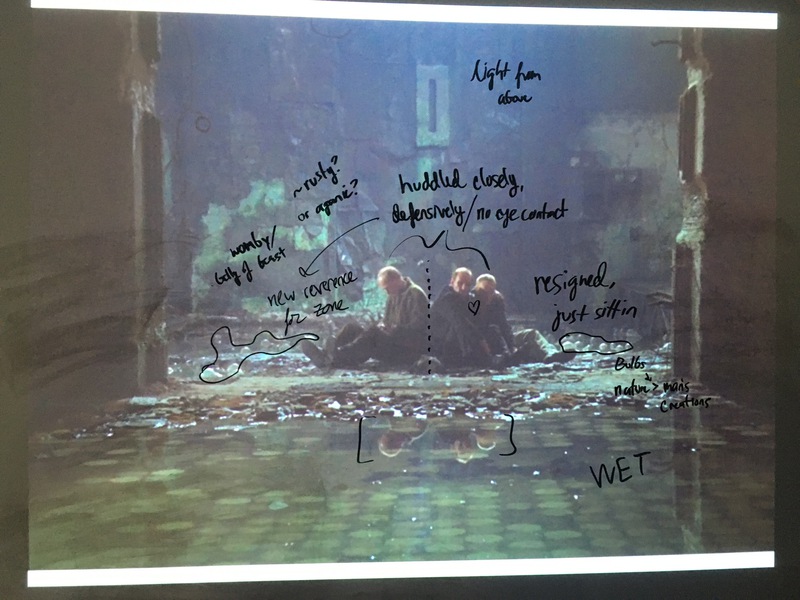

In the “Transmedial Chernobyl” unit, we read the Strugatsky Brothers’ Roadside Picnic about so-called “stalkers” who trespass into a dangerous zone. Although this science-fiction novel was written prior to the Chornobyl accident, its representation of intergenerational trauma as well as of the perils of scientific inquiry resonates with Chornobyl’s legacy. We held a screening of Andrei Tarkovsky’s acclaimed film Stalker, an adaptation of Roadside Picnic. Students then played S.T.A.L.K.E.R.: Shadow of Chernobyl to consider the ethical implications of virtual immersion in the Chornobyl landscape through video games.

Looking at such representations of Chornobyl prepared us to explore appropriations of the catastrophe such as Bradley Parker’s horror film Chernobyl Diaries, disaster tourism, and excerpts from young adult novels, mystery books, and monster stories that instrumentalize Chornobyl as a plot device. Identifying how such approaches commercialize the story of Chornobyl compelled us to question whether engaging with catastrophe and visiting sites of death can facilitate meaningful reflection.

In our study of Chornobyl as an environmental disaster, we endeavored to improve our scientific understanding of the catastrophe’s ecological effects and to decenter the human perspective. In the documentary An Invisible Enemy, we listened to the Sámi people speak about how radioactive fallout from Chornobyl has compromised their economy based on reindeer herding and ability to transmit their culture. Historian Kate Brown’s Manual for Survival exposed significant gaps in our understanding of Chornobyl’s impact on the environment. Michael Marder and Anais Tondeur’s innovative project The Chernobyl Herbarium compelled us to focus on the meditative silence of plant life and inspired us to build our own Bryn Mawr Herbarium with photos of flowers, trees, and weeds around campus.

When we listened to and discussed Jakob Kirkegaard’s 4 Rooms, we also recorded soundscapes to explore what we can hear around campus and to consider what these sounds can tell us about a place: the entrance to Canaday Library, Old Library, outside Merion Hall, outside Taylor Hall.

We closed the course by explicitly linking our analysis of Chornobyl’s ecological effects to society’s complicity in the climate crisis, and our class ended with the following questions:

- Do tragedies like Chornobyl need to have a meaning?

- What are the limitations of language in light of catastrophe?

It is our hope that this digital installation will both enable us to articulate some of our own responses to the political, linguistic, scientific, and existential ruptures that Chornobyl has caused and to catalyze ongoing dialogue. Thank you for joining us in this process.

The original version of this page was written by Grace Sewell and updated with her kind permission.

Site supported by Digital Scholarship at Bryn Mawr College