“I killed her. I. She. Saved. My little girl saved me, she took the whole radioactive shock into herself, she was like a lightning rod for it.”

- Lyudmilla Ignatenko

Lyudmilla Ignatenko, the wife of fireman Vasily Ignatenko, first on the scene when reactor No. 4 of the Chornobyl Nuclear Power Plant exploded, is a well-known Chornobyl survivor and her description of her husband’s death in her 1996 interview with Svetlana Alexievich became popularized in the 2019 HBO Chornobyl miniseries.

Shortly following the immense exposure from the reactor fire, Vasily was evacuated to Moscow and treated in Hospital No. 6, which specialized in radiology. While six months pregnant, Lyudmilla found her husband in Moscow and took care of him. Despite the insistence of doctors, nurses, and even her husband to stay away, Lyudmilla remained with Vasily and cared for him until he died a little over two weeks later. Lyudmilla and Vasily decided that if they were to have a boy, to name him Vasily, and if they had a girl, call her Natasha. A few months later, Lyudmilla gave birth to Natasha, who died soon after and was buried next to her father in the Moscow Mitinskoe Cemetery.

“A young pregnant woman died suddenly, without any diagnosis. A little girl hanged herself, she was in fifth grade. Just…for no reason. A little girl. There’s no diagnosis for everything—Chornobyl. People get mad at us: ‘You’re sick because you’re afraid. You’re sick from fear. Radiophobia.’ But, then why do little girls get sick and die? They don’t know fear, they don’t understand it yet.’”

- Nina Konstinovna

Mothers near and far from the Chornobyl disaster feared not only for their lives after radiation exposure but for what would happen to their children as well. Radiophobia, the fear of radiation and the hysteria of its potential consequences, in the context of Chornobyl, provided widespread anxiety to those affected. As more people understood the long-term effects of radiation exposure, women especially began to have immense anxiety regarding the impact of exposure on themselves and their children, born and unborn.

Many women in Alexeivich’s compilation of Chornobyl memoirs shared their fears of radiation regarding their children. These narratives testify to the tragedies caused by Chornobyl and depict a bigger picture of its consequences. The supplemental medical information and statistics on birth outcomes and abortion rates intend to strengthen these narratives and confirm that the fear of the unknown affected mothers’ choices for generations. Fear and anxiety are strong emotions that heavily influence the responses and choices of mothers. Based on the fears and experiences of women and mothers from Chornobyl, there was good reason to believe the lives of their children were at stake. The story of Larisa Z., another mother interviewed by Alexeivich, is an example of mothers’ fear regarding their children and their perceived role in the outcomes of their children’s health.

“In four years she’s had four operations. She’s the only child in Belarus to have survived being born with such complex pathologies. I love her so much. I won’t be able to give birth again. I wouldn’t dare. I came back from the maternity ward, my husband would start kissing me at night. I would lie there and tremble: we can’t, it’s a sin, I’m scared.”

- Larisa Z.

Larisa’s fear is entirely appropriate given that she already gave birth to a severely disabled daughter, which she believed and confirmed later to be caused by radiation. However, what is more concerning is her perceived role in what she thought to be a “sin”—having children. This perceived sin of having children was not a singular experience but a collective mindset mothers shared when dealing with the consequences of Chornobyl.

“I’m afraid. I’m afraid to love…I can’t get rid of that feeling. I’ll never rid myself of it. Do you know that it can be a sin to give birth?’”

- Katya P.

Based on this line of reasoning, the mothers of Chornobyl believe that not only are they responsible for the poor health outcomes of their children, but they are involved in the sin of procreation and bringing life into the world. Despite Chornobyl “just happening” to these mothers, mothers certainly felt like they could not let Chornobyl “happen” to their children. As a result, the mothers of Chornobyl have a fractured relationship with their children. This sense of guilt is rooted in a mother’s responsibility for their children, which might stem from the ideology that women act as the creators of life. The origins of this feeling could be rooted in religious beliefs influenced by Russian Orthodoxy. Nonetheless, with such an immense burden to raise a child comes an overwhelming instinct to bear sole responsibility, which may contribute to why mothers believe they are inherently involved in a sin.

Many mothers tried to contextualize their fears and anxiety in hopes of relieving the strain on their relationship with their children. Many other Chornobyl survivors attempted to compare the fear they were experiencing with the fear that emerged from World War II; however, mothers expressed in their narratives that this was incomparable.

“People talk about the war generation, they compare us to them…They weren’t afraid of anything, they wanted to live, learn, have kids. Whereas us? We’re afraid of everything. We’re afraid for our children, and for our grandchildren, who don’t exist yet. They don’t exist, and we’re already afraid.”

- Nadezhda Afanasyevna Burakova

When narrating Chornobyl, many people describe their experiences as a war because there was no precedent for an event like this. These mothers watched the death of their children caused by an invisible enemy—radiation. Mothers felt they were responsible for the casualties caused by this invisible enemy for generations to come. Thus, mothers experienced this immense responsibility for generations of their descendants, which fractured the structure of motherhood itself. The structure of motherhood is based on the idea that mothers should solely care for their immediate children rather than the outcomes of their great-grandchildren.

“I heard—the adults were talking—Grandma was crying—since the year I was born [1986], there haven’t been any boys or girls born in our village. I’m the only one. The doctors said I couldn’t be born. But my mom ran away from the hospital and hid at grandma’s. So I was born at grandma’s. I heard them talking about it. I don’t have a brother or sister. I want one. Tell me, lady, how could it be that I wouldn’t be born? Where would I be? High in the sky? On another planet?”

- Child of Chornobyl

Many women feared the consequences of giving birth and carrying their children to term. With the fear of radiation also came the fear of infertility, miscarriage, and stillbirth. What distinguishes these birth outcomes is that they occur at different stages of motherhood. Infertility describes the inability to conceive a child, which prevents women from entering motherhood altogether. On the other hand, miscarriage and stillbirth happen during motherhood and describe pregnancy loss at different stages in gestation. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, miscarriage is defined as the loss of a baby before the 20th week of pregnancy, and stillbirth is the loss of a baby at 20 weeks of pregnancy or later.

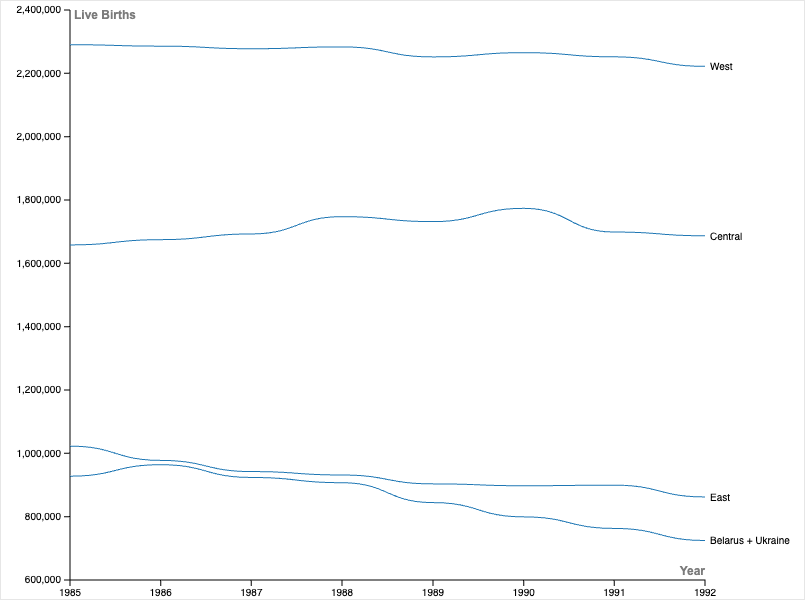

The International Epidemiological Association compiled data on live births and stillbirths in Europe to see the pre- and post-Chornobyl differences. As seen in Figure 1, there was a decline in live birth rates in Belarus and Ukraine—the countries most affected by the Chornobyl accident. Based on the narratives of Chornobyl mothers, conclusions can be drawn that this decline in live birth rate was because of the increase in infertility and the intentional abstinence of mothers. Additionally, the study found a relatively significant increase in the Eastern European stillbirth rate proportional to the live births from 1986 to 1992. Thus, this data shows that the fears of mothers regarding being infertile or having stillbirths were not an irrational fear but came true.

Even if mothers did have a baby that survived birth, the anxiety surrounding their children certainly did not leave. In many cases, mothers made sure to intensely examine their child after delivery out of fear that their child would be born disabled or “alien-like.” Disabilities could range from genetic mutations, congenital heart disease, autoimmune disorders, connective tissue disorders, cancers, and mental and behavioral disorders.

“It’s been a long time since I’ve seen a happy pregnant woman. A happy mother. One gave birth recently, as soon as she got herself together she called, ‘Doctor, show me that baby! Bring him here.’ She touched the head, forehead, the little body, the legs, the arms. She wants to make sure: ‘Doctor, did I give birth to a normal baby? Is everything all right?’ They bring him in for feeding. She’s afraid: ‘I live not far from Chornobyl. I went there to visit my mother. I got caught under the black rain.’ She tells us her dreams: that she’s given birth to a calf with eight legs, or a puppy with the head of a hedgehog. Such strange dreams. Women didn’t used to have such dreams. Or I never heard them. And I’ve been a midwife for thirty years.”

- Irina Yurevna Lukashevich

Once again, the relationship between mothers and their children becomes fractured because mothers categorize their children into “normal” and “other.” Mothers not only worried about the health of their children, but they isolated themselves and hesitated to accept their children. One would think mothers accept and embrace their children no matter what because of maternal instinct; however, this fractured relationship dissolved mothers’ instinct to accept their children.

A clinical explanation for why Chornobyl mothers isolate and don’t accept their children right away could be a result of postpartum depression (PPD). According to the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, PPD is when mothers experience sadness, anxiety, tiredness, and hopelessness for longer than two weeks after giving birth. It is typical to experience some extent of “baby blues” after giving birth. However, PPD is a serious mental health condition and can cause mothers to feel detached from their babies and their loved ones and may not feel love or care for their children. There is a higher risk of having PPD for mothers who are experiencing other stressful life experiences; thus, PPD could have been higher in Chornobyl mothers, but there has not been much research on this topic.

Furthermore, as a result of this fractured relationship, mothers were more likely to want to completely disassociate from their children through abortions, whether doctors advised them or came to this decision on their own. Arguably, these mothers didn’t want their children to be another consequence of Chornobyl. Potentially, they also tried to save themselves from the guilt and perceived sinfulness of raising a Chornobyl child described by some mothers previously.

“We were expecting our first child. My husband wanted a boy and I wanted a girl. The doctors tried to convince me: ‘You need to get an abortion. Your husband was at Chornobyl.’ He was a truck driver; they called him in during the first days. He drove sand. But I didn’t believe anyone. The baby was born dead. She was missing two fingers. A girl. I cried. ‘She should at least have fingers,’ I thought. ‘She’s a girl.’”

- Widow of a liquidator

“Animals, even cockroaches, they know how much and when they should give birth. But people don’t know how to do that, God didn’t give us the power of foresight. A while ago in the papers it said that in Belarus alone, in 1993 there were 200,000 abortions. Because of Chornobyl. We all live with that fear now.”

- Aleksandr Revalskiy

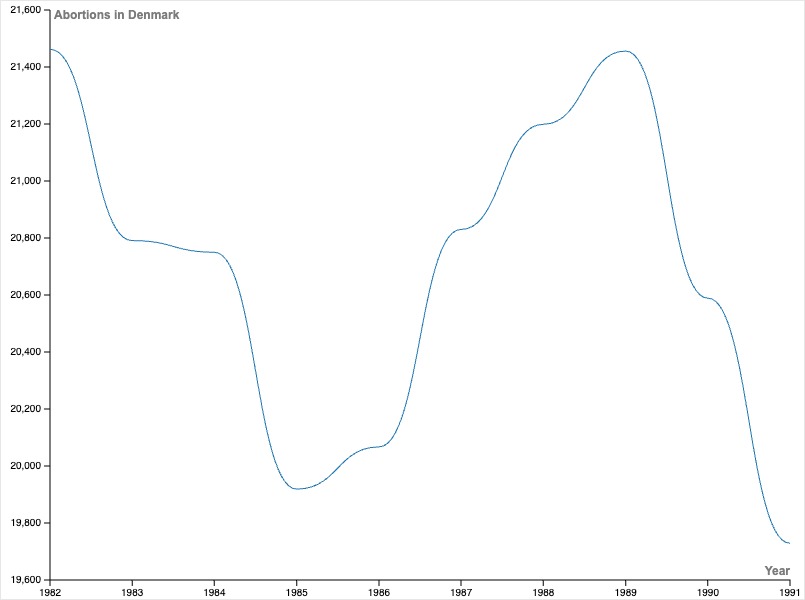

In 1988, the Ministry of Public Health of the Soviet Union reported 6.5 million recorded legal abortions, which exceeded the 5.6 million live births that year. Mothers intensely pondered the decision to pursue an abortion in places that ranged from low to high levels of radiation. For example, Copenhagen, which is 1,107.00 mi (1,781.54 km) from the Chornobyl site, found a very low increase in the risk of birth defects due to the amount of radiation in Denmark. Denmark, which has permitted abortion until the end of the twelfth week of pregnancy since 1973, conducted a study to see how the Chornobyl disaster affected the abortion rate. This study addressed how the fear and anxiety surrounding Chornobyl might have contributed to the higher abortion rates shortly after the accident.

As seen in Figure 2, there was a slight observed uptick in abortion rates after the Chornobyl accident in 1986 in Denmark. In addition, the study found that there were stark differences between county abortion rates, especially in metropolitan areas. It concluded that the public fear of radiation could partially explain the increased abortion rates. Similar studies were conducted in Sweden and Austria in the early 1990s and found that there was little evidence to support that the Chornobyl accident was the cause of increased abortions. However, the study in Sweden noted that many Swedish mothers expressed concern about the accident’s consequences during intake at abortion appointments. Thus, the narratives of Chornobyl mothers are critical to putting these statistics into context because these narratives explain the emotions and thought processes of the women, which are absent in abortion statistics.

Ultimately, the fractured relationship between mothers and their children is the result of the fear and anxiety caused by the Chornobyl accident. Chornobyl forever changed the mindset of mothers and introduced a generation of motherhood filled with guilt, shame, and detachment. There is no simple solution to changing this mindset of mothers, and repairing the fractured relationship would take generations to overcome. Despite the trauma, many mothers wanted to move on and put this behind them. For example, Lyudmilla Ignatenko remarried later in life and became pregnant; meanwhile, friends, family, and doctors said her body could not handle the stress of carrying another child. She then gave birth to a son, Andrei, who was perfectly healthy and whom she greatly cherished.

Bibliography

-

Alexievich, Svetlana. Voices from Chernobyl: The Oral History of a Nuclear Disaster. Tchernoblyskaia Moltiva, 1997.

-

David, Henry P. “Abortion in Europe, 1920-91: A Public Health Perspective.” Studies in Family Planning, vol. 23, no. 1, 1992, pp. 1–22. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/1966824.

-

Haeusler, M C et al. “The influence of the post-Chernobyl fallout on birth defects and abortion rates in Austria.” American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology vol. 167, no. 4 Pt 1, 1991, pp. 1025-1031. doi:10.1016/s0002-9378(12)80032-9

-

Knudsen, LB. “Legally-Induced Abortions in Denmark after Chernobyl.” Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy, vol. 45, no. 6, Jan. 1991, pp. 229–231.

-

Odlind, V., and A. Ericson. “Incidence of legal abortion in Sweden after the Chernobyl accident.” Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy, vol. 45, no. 6, 1991, pp. 225-228. doi:10.1016/0753-3322(91)90021-k

-

“Postpartum depression.” Office on Women’s Health at the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services.

-

Scherb, H. et al. “European stillbirth proportions before and after the Chernobyl accident.” International Journal of Epidemiology vol. 28, no. 5, 1999), pp. 932-940.

-

“What is Stillbirth?” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

-

Wikipedia contributors. “Radiophobia.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 13 Oct. 2023. Web.

-

Wikipedia contributors. “Vasily Ignatenko.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 10 Sep. 2023. Web.

Fay Koyfman ‘24 is a chemistry and Russian major at Bryn Mawr College.

RUSSB220 Chornobyl, Bryn Mawr College, Fall 2023

Licensed under CC BY-ND 4.0.