All translations and annotations by Grace Sewell. Thank you to Frank Kenny (Swarthmore Class of 2020), Professor José Vergara, and Professor María-Luisa Guardiola for their thoughtful suggestions and revisions.

Introduction

In The Memory of Catastrophe, historians Peter Gray and Kendrick Oliver argue that “acute cultural rupture [is] the identifying mark of the catastrophic.” 1 This idea offers a valuable framework through which to understand the Chernobyl disaster. Chernobyl is not only a historical event, but an active process of disruption that resonates across geographical and cultural contexts. What kinds of “rupture” has Chernobyl caused, and where? How do catastrophes such as Chernobyl resist interpretation and resolution? What is the power of language and art in the face of catastrophe? Can the study of Chernobyl transform how we interpret and act in the face of other historical and contemporary crises? What barriers does Chernobyl pose to ethical and effective communication and expression?

To facilitate reflection on these topics and others, I have generated original translations of poetry written in Spanish, Russian, and Ukrainian. Each poem is annotated so as to track the key symbols, ideas, and references that inform the authors’ approach to the Chernobyl mythology. While the poems are annotated individually, they are meant to be read in dialogue with each other. The fragmentary and nonlinear form of this project simulates the dislocation that continues to shape individual and collective memory of Chernobyl.

Prior to interacting with the poems, consider the following excerpt from Michael M. Naydan’s translation of an untitled poem by acclaimed Ukrainian poet and Chernobyl activist Lina Kostenko, which inspired the name of this project.2

A terrifying kaleidoscope:

at this moment someone somewhere died.

At this moment. At this very moment. Each of every minute.

A ship has broken apart. The Galapagos Islands burn.

And the bitter star-wormwood descends above the river Dnieper.

As part of a kaleidoscope of disaster, Chernobyl compels us to investigate how perception and memory break down in the “aftermath” of catastrophe. Poetry, therefore, provides the ideal lens through which to encounter the linguistic, historical, and political reflections and tensions associated with Chernobyl.

Types of Annotations

Each annotation is tagged according to its type. “Author” annotations provide brief biographical information about the authors of each poem. “Context” annotations serve to provide basic historical and background information to frame key figures, ideas, and concepts that may be unfamiliar to the audience. “Analysis” annotations, which often reference corresponding “Context” annotations, offer my own readings of the symbols and metaphors in the poem. “Translation” annotations highlight fragments of the poems that were especially difficult to translate and explain the choices that I made. I have also included “Discussion Question” annotations, which directly invite the audience to reply to the prompt in order to facilitate ongoing dialogue. It is important to note that I have intentionally not provided “synthesis” annotations after each individual poem, in order to allow the reader to experiment with different ways of moving through the texts. That being said, at the bottom of the page, you will find a concluding section entitled “Reading Kaleidoscopically for the Future” which positions the themes of the poems in relation to each other and suggests a way forward for reader and writer alike.

POEMA 36 – Chernóbil (1986)

Hernán Urbina Joiro

No lo compartieron

hubo que indagarlo,

Cortina de hierro,

en Suecia encontraron

a un día del estrago

radiación de frontera

igual en Finlandia

como en Alemania,

Cortina de hierro,

no podías borrarlo.

Moscú: Apenas fue antier

abril 26

dos días después

se hizo el anuncio,

pequeño revés,

solución en curso.

Y punto.

La nube radioactiva

burló tu Cortina,

Europa alcanzó.

Habla Gorbachov:

Escuchen, en mayo

terrible explosión

gran afectación.

El mundo abismado.

Miles de muertos

que el tiempo aumentará

500 veces más

que en Hiroshima, según expertos.

No resistió la prueba el viejo reactor.

¿Cuántos reactores más nos ponen en riesgo?

Cortina de Hierro,

tu contradictor, Occidente, corre a tu favor.

¿No había con qué ponerle hormigón

con amarillo acero

a un sarcófago certero

contra la radiación

que no pondrá en control una Cortina de Hierro?

Nadie sabía tu secreto

hoy la revelación

cuestiona tu enorme imperio.

¿Sólo había para control

de semejante explosión

una Cortina de Hierro?

Poem 36 – Chernobyl (1986)

Hernán Urbina Joiro

They did not share it,

we had to question it.

Iron Curtain,

One day after the destruction

in Sweden they found

boundary radiation;

the same in Finland

as in Germany, too.

Iron Curtain,

You could not erase it.

Moscow: It was just yesterday

April 26

Two days later

The announcement was made.

Minor setback,

Solution in progress.

Full stop.

The radioactive cloud

ran circles around your Curtain,

and caught up to Europe.

Gorbachev speaks:

Listen, in May,

Terrible explosion,

incredible pretense.

The world sunk into an abyss.

According to experts,

time will increase the thousands of dead

500 times more

than in Hiroshima.

The old reactor did not withstand the test.

How many more reactors put us at risk?

Iron Curtain,

Your antagonist, the West, works to your advantage.

Wasn’t there a way to put concrete

and yellow steel

in a radiation-proof

sarcophagus

that would not put an Iron Curtain in control?

Nobody knew your secret

Today the revelation

questions your enormous empire.

Was all that existed to control

such an explosion

an Iron Curtain?

Думы о Чернобыле

Андрей Вознесенский

Человек

Прости мне,

человеку,

человек, –

история, Россия и Европа, –

что сил слепых

чудовищная проба

приходится

на край мой

и мой век.

Прости,

что я всего лишь

человек.

Надежда,

коронованная Нобелем,

Как страшный джинн,

очнулась над Чернобылем.

Простите, кто собой

закрыл отсек.

Науки ль,

человечества ль вина?

Что пробило

и что ещё не пробило,

и что предупредило

нас в Чернобыле!

А вдруг –

неподконтрольная война?

Прощай,

расчет на легкое житье

Опомнись, мир,

пока ещё не поздно!

И если человек –

подобье божье,

неужто бог– подобие моё?

Бог - в том,

кто в заражённый

шёл объект,

реактор потушил,

сжёг кожу и одежду.

Себя не спас.

Спас Киев и Одессу.

Он просто поступил,

как человек.

Бог – в музыке,

написанной к фон Мекк.

Он – вертолётчик,

спасший и спасимый,

и доктор Гейл,

ровесник Хиросимы,

в Россию

прилетевший человек.

Thoughts on Chernobyl

Andrei Voznesensky

Humanity

Forgive me,

a human,

Humanity –

history, Russia, and Europe –

that the monstrous test

of the blind forces

happened to fall

on my land

and my era.

Forgive

that I am only

human.

Hope,

crowned by the Nobel Prize

awakened over Chernobyl

like a strange jinn.

Forgive me, he who sealed the

compartment with his body.

Is it the fault of science

or of humanity?

What has broken through and

what has still not broken through and

what warned

us in Chernobyl!

What if this is

uncontrollable war?

Farewell,

to the expectation of easy living.

Come to your senses, world,

before it’s too late!

If man is the

likeness of God

is it possible that God is also my likeness?

God is in

he who went to the contaminated object;

He who extinguished the reactor;

Whose clothing and skin burned.

He did not save himself.

He saved Kiev and Odessa.

He simply acted

like a human.

God is in the music

written to Von Mekk.

He is the helicopter pilot

who saved and is saved,

He is Doctor Gale,

The contemporary of Hiroshima,

the man who flew into

Russia.

Больница

Мы потом разберёмся:

кто виноват,

где

познанья

отравленный плод?

Вена ближе Карпат.

Беда вишней цветёт.

Открывается новый взгляд.

Почему

он в палате

глядит без сил?

Не за золото, не за чек.

Потому

что детишек

собой заслонил,

Потому что он –

человек.

Когда

робот не смог

отключить беды,

он шагнул в заражённый

отсек.

Мы остались живы –

и я, и ты –

потому что он – человек.

Неотрывно глядит,

как Феофан Грек.

Мы одеты в спецреквизит,

чтоб его собой

не облучить,

потому что он – человек.

Он глядит на тебя,

на меня,

на страну.

Врач всю ночь

не смежая век,

костный мозг

пересаживает ему,

потому что он – человек.

Донор тоже не шиз –

раздавать свою жизнь.

Жизнь одна –

не бездонный парсек.

Почему же он смог

дать ему костный мозг?

Потому что он – человек.

Он глядит на восход.

Восемь душ его ждёт.

Снится сон –

обваловка рек.

Верю, он не умрёт,

это он – народ,

потому что он – человек.

Hospital

Later we will determine:

Who is to blame;

Where is the

poisoned fruit

of knowledge?

Vienna is closer than the Carpathians.

Тhe trouble blooms with the sour cherry

A new view opens.

Why

does he look exhausted

in the ward?

Not for gold, not for a check.

Because he shielded the

dear children

himself;

because he is

a human.

When

the robot could not

shut down the troubles,

he stepped into the contaminated

compartment.

We remained alive,

you and I both,

because he is a human.

He stares uninterruptedly,

like Theophanes the Greek.

We are dressed in specialized equipment

to avoid

irradiating him

because he is a human.

He is looking at you,

at me

at the country.

All night long,

without shutting his eyes,

the doctor transplants

bone marrow to him,

because he is a human.

The donor is not crazy enough, either,

to give away his life.

Life alone

is not an unfathomable parsec.

How was he able

to give him bone marrow?

Because he is a human.

He looks at the sunrise.

Eight souls await him.

He’s dreaming a dream –

river embankment.

I believe he will not die,

he – the people,

because he is a human.

З «Летючих катренів», #2

Ліна Костенко

Ми – атомні заложники прогресу,

вже в нас нема ні лісу,

ні небес.

Так і живем –

од стресу і до стресу.

Абетку смерті маємо –

А Е С.

From Volatile Quatrains, #2

Lina Kostenko

We, the atomic hostages to progress,

no longer have the forest

nor the heavens.

So we live –

from one problem to the next.

We have the alphabet of death:

N. P. S.

Reading Kaleidoscopically for the Future

In the introduction to this project, I contend that Chernobyl poetry must be read as part of a kaleidoscope of disaster. This kaleidoscope destabilizes and complicates the relationship between language, history, and memory in light of catastrophe. As you likely encountered while navigating through these annotated poems, these literary responses to Chernobyl center around different kinds of lack. The poet and reader cannot resolve these breakdowns and absences, even as they collaboratively propose and test potential solutions through language and metaphor.

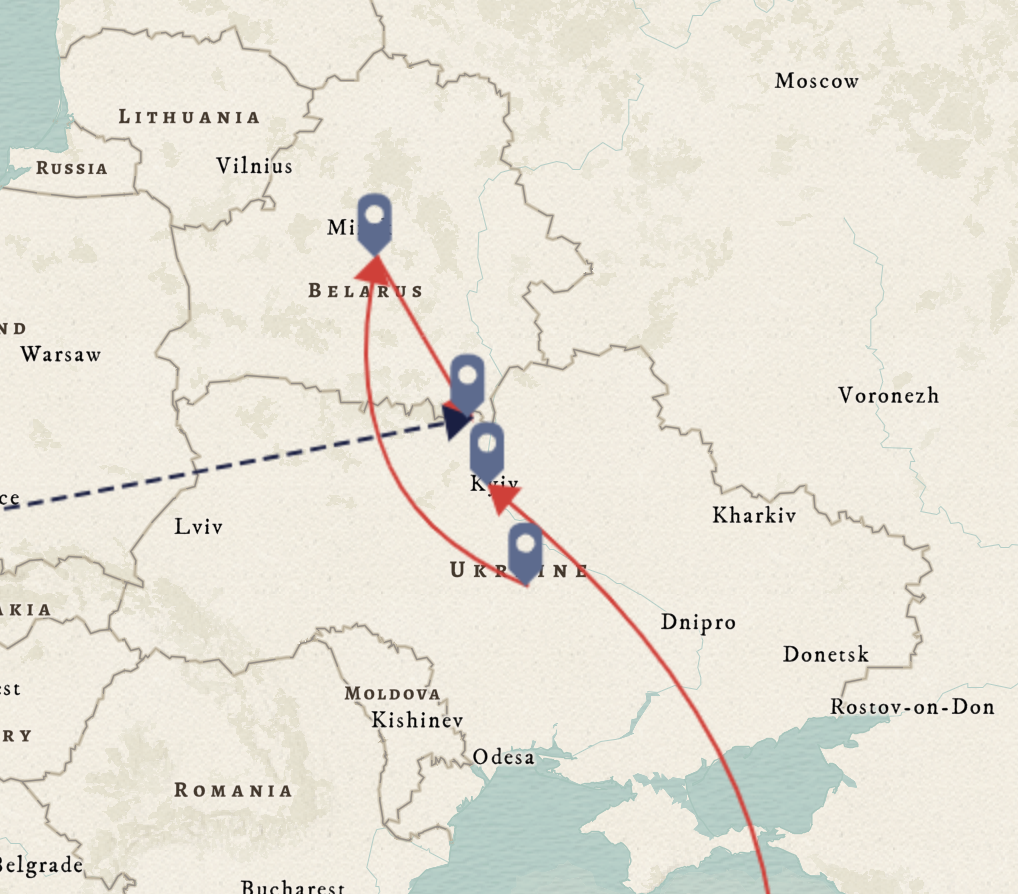

In Hernán Urbina Joiro’s poem, Chernobyl is the catalyst for a loss of political control that exacerbates the preexisting tensions between “East” and “West.” While Urbina Joiro places Chernobyl within a transnational context, this poem does not interrogate how the disaster resonates with nuclear issues and political corruption outside of Eastern Europe. As such, the poem absolves the (Western) audience of the need to reflect on their relationship to the catastrophe and their complicity in the systems that allow for such disasters to happen.

Andrei Voznesensky’s poem “Thoughts on Chernobyl” draws compelling connections between all of “humanity” and the Chernobyl catastrophe, thereby expanding the limited approach to accountability and culpability that we encounter in Urbina Joiro’s poem. The speaker tries to respond to Chernobyl by accepting personal responsibility for the disaster and expressing his belief in the sacredness of the heroes who intervened. However, as the poem continues, the question of “Who is to blame” becomes more pressing and more difficult to resolve. Thus, “Thoughts on Chernobyl” further complicates the delineation between hero, victim, and perpetrator.

While Voznesensky’s poem questions the possibility of absolution for self and society alike, Lina Kostenko defines Chernobyl as a cause of profound spiritual loss. She traces the origins of this alienation to the “alphabet of death” associated with nuclear power. No form of linguistic expression, including Kostenko’s poem, can offer compelling solutions to transnational disaster. According to her reading, nuclear catastrophe itself has the final word.

I came into this class asking whether it is possible to fix the broken and deficient linguistic framework that Kostenko references in order to successfully interpret and recover from catastrophe. I have shifted the focus of this question significantly as a result of my time in the course and my experience working on this project. Instead of seeking to correct individual representations of catastrophe, we must fundamentally transform how we “read” disaster by intentionally exposing language and memory to the disruptive and disorienting lens of the kaleidoscope. In this way, it becomes possible to acknowledge, link, and amplify the silences, gaps, and fragments that structure these responses. The “Chernobyl kaleidoscope” is not simply a collection of poems and perspectives. Instead, the kaleidoscope calls for ongoing participation in an active, dynamic, and self-aware reading process that extends beyond the scope of this installation.

Works Cited

-

Peter Gray and Kendrick Oliver, introduction to The Memory of Catastrophe (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2004), 8. ↩

-

Lina Kostenko,“Untitled,” translated by Michael M. Naydan in Shifting Borders: Eastern European Poetries of the Eighties, ed. Walter Cummins (Rutherford: Associated University Presses, 1993), 375. ↩

Grace Sewell ‘22 is an Honors Russian Major, Course Spanish Major, and Honors Spanish Minor from Salem, Oregon. Outside of the classroom, she is involved in the Swarthmore Project for Eastern European Relations and Swarthmore Queer Union.

RUSS043 Chernobyl: Nuclear Naratives and the Environment, Swarthmore College, Spring 2020