People

Speakers

The original slate of speakers, as indicated in the January 19th telegram between Annamae Grant '31 and W.E.B. Du Bois, was Walter White, Alain Locke, Philip Randolph, J.B. Matthews, Will Alexander, Frank Crosswaith, and Mordecai Johnson.1 In the end, Will Alexander, Frank Crosswaith, and Mordecai Johnson did not attend the conference. Alice Dunbar Nelson and Ira Reid, who were not listed among the original panelists, did attend and gave talks.

While we can look back now on the biographies of the likes of W.E.B. Du Bois and see their important contributions, what did the students of the day know about these speakers? By 1931, in what areas were the speakers active and for what were they known? By conducting outside research and analyzing how publications reporting the event referred to the speakers, we can get an idea of what issues they addressed and why the committee might have wanted people to speak on the topic of economic conditions.

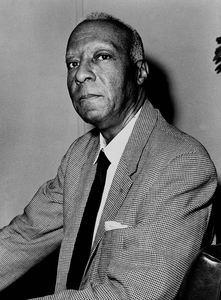

In 1931, Walter White was the Secretary of the NAACP. A portion of his talk was reported by The College News to be dedicated to the terroristic act of lynching.1 At the time, White was notably dedicated to anti-lynching efforts, sometimes going undercover at KKK rallies to gather information for the NAACP.2

Alain Locke was a professor of philosophy at Howard University. Conference-related publications reported Locke’s emphasis on African American culture and art. Locke was later credited as a leading figure of the Harlem Renaissance.3

Philip Randolph was an organizer of the Brotherhood of Pullman Car Porters, the first labor union for the Pullman Car Company, a large employer of African American workers. Randolph devoted a portion of his talk to unions. At a time when African Americans were excluded from many unions and protection from labor laws and subject to widespread racial discrimination, Randolph was an outspoken labor rights and civil rights activist.4

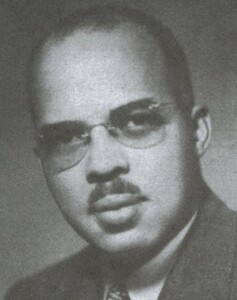

Ira Reid was the director of the research department of the National Urban League. Around the time of the conference, Reid had conducted influential studies on the economic and social conditions of African Americans. In 1947, Reid would become Haverford College’s first African American professor.5

Alice Dunbar Nelson was the executive secretary of the Interracial Peace Committee of the Society of Friends, a Quaker organization. A few weeks prior to the 1931 conference, Nelson had left her position in the Interracial Peace Committee of the Society of Friends and would continue to work as a journalist, writer, and poet as well as educator, women’s rights activist, and civil rights activist.6

J.B. Matthews was the secretary of the Fellowship of Reconciliation, a pacifist religious organization, and the conference’s only white speaker. By 1931, Matthews had already distinguished himself as an accomplished linguist, active pacifist, and member of the Socialist Party of America.7

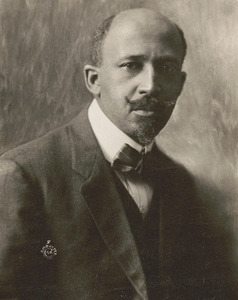

In 1931, W.E.B. Du Bois was the editor of The Crisis, the NAACP’s monthly magazine, an influential publication covering race relations and African American culture. Du Bois was a founding member of the NAACP, a groundbreaking sociologist, and a sought-after public speaker. He received numerous invitations to address different institutions’ Liberal Clubs, including those at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Haverford College, Swarthmore College, and George Washington University.8

1. "Negro Intellectuals Stress Inequality of Opportunity for Race in All Fields," The College News, April 29, 1931.↩

2. Biography.com Editors, “Walter White,” Biography.com, A&E Networks Television, accessed May 20, 2020↩

3. Carter, Jacoby Adeshei, "Alain LeRoy Locke," The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by Edward N. Zalta, Summer 2012 edition.↩

4. “A. Philip Randolph: AFL-CIO,” AFL-CIO, accessed August 26, 2020.↩

5. "At Haverford," Ira de Augustine Reid, Haverford College Libraries, accessed August 26, 2020.↩

6. Dunbar-Nelson, Alice Moore, and Gloria Hull, Give Us Each Day: The Diary of Alice Dunbar-Nelson, New York: Norton, 1986, via Internet Archive, accessed August 28, 2014.↩

7. Dawson, Nelson L., “From Fellow Traveler to Anticommunist: The Odyssey of J. B. Matthews,” The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society, 84: 3 (1986): 280–306, via JSTOR, accessed August 6, 2020.↩

8. “NAACP History: W.E.B. Dubois,” NAACP, accessed August 26, 2020.↩